Rangiaowhia was vitally important to the people of the area because it was a centre of economic growth and trade. The market gardens supplied much of the produce sold in Auckland and afar. Raukawa believe that when the Crown attacked Rangiaowhia on 21 February 1864, a massacre of refugees and non-combatants occurred. Accounts of the massacre saw Crown forces including militia unload a barrage of gunfire into the village, trapping the villagers within their whare.

The battle at Ō-Rākau began in earnest on the 31 March 1864 and concluded on the 2 April 1864. Leading the first British attack on Ō-Rākau was Brigadier-General G. J Carey, who was met with heavy resistance from the pā.

Video transcript

Robert Joseph:

‘It’s actually not recorded in a lot of our “official history books”. They don’t record what happened here and many of them actually down played what happened here.

This place was actually known as the granary of the North Island. It was a huge hub of economic development and prosperity. But Māori signed the declaration there, so that they could continue international trade. This was truly an economic heart not only for Tainui but for the country.

This place had this church, this is all that’s left now the Anglican church. Te Hāhī Katorika, a Catholic church and a Māori whare karakia as well. They had a big race course. Some of the early Europeans when they came here they were actually surprised at the wealth that was here. They wanted this land so they introduced a policy of confiscation. If Māori aren’t gonna sell it, we’re just gonna take it by law.

The battles that occurred so there’s Koheroa, Meremere, Rangiriri, Pāterangi, Rangiaowhia then Ō-Rākau. But what’s important is we need to acknowledge our history, because it’s ours, no matter how disturbing. And that is what Rangiaowhia is about whānau. That’s what we are striving to do here. Tell the full picture and it’s nigh impossible to tell it all, but tell what best we can, what happened. Because as one of the themes of this whole kaupapa, Me Maumahara Tātou – we must remember. We must remember what happened here, because if we don’t remember, we don’t learn the lessons and then we continue to do the silly things against each other. So, we must remember what happened here whānau.’

Nigel Te Hiko:

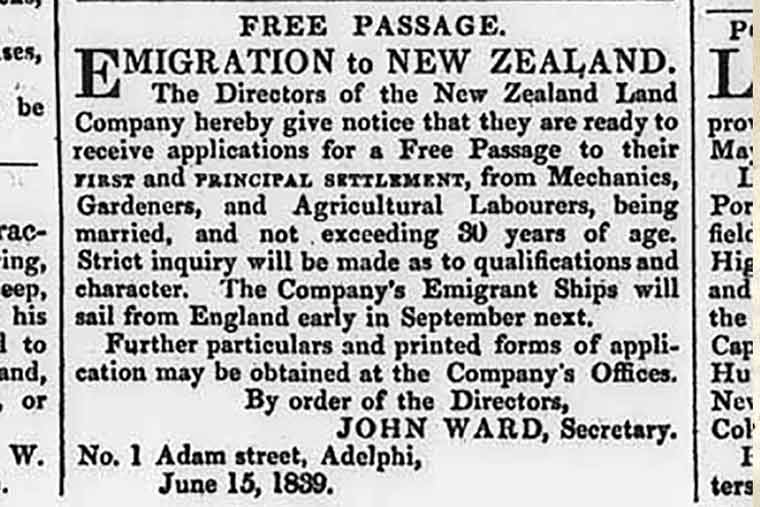

‘What we have now, is that we’ve all come together to start looking at the NZ Wars. So, in 1863 the Crown crossed the Mangataawhiri stream, a further north of us towards Tuakau, they crossed the Mangaatawhiri stream, which essentially meant that they invaded the Waikato. This wasn’t a simple, “we’re moving people down here.” This was an actual invasion.

Back in 1863, Governor Grey had heard that these Waikato Māori were going to attack Auckland, it was a lie. Rumour. On the 9th July 1863, the Governor issued a proclamation, and on that proclamation, he said “that if you are a Māori in that Northern Waikato area, you must swear allegiance to the Crown, if you do not swear allegiance to the Crown, then you are going to be evicted from your home”. Two days they were given in order to swear allegiance, they didn’t, the invasion started.’

Paraone Gloyne:

‘Now I want you to close your eyes. Close your eyes. I want you to imagine a grove of peach trees here. Close your eyes and imagine. I want you to imagine cornfields and wheat and orchards full of ripe succulent fruit. I want you to imagine gardens as far as the eye could see around here. I want you to imagine tamariki running around. I want you to imagine a racecourse. I want you to imagine two flour mills where they milled their own flour here. I want you to imagine you hear the bullets. I want you to imagine you can hear the horse hooves of the cavalry. I want you to imagine you can hear General Von Tempsky saying “Fire!” I want you to imagine your koro running out with a white blanket as a sign of peace. “Bang!” I want you to imagine that they shot him. I want you to imagine that their house caught on fire. I want you to imagine that those people in that house were burnt alive.

Open your eyes. That’s what happened here at Rangiaowhia. So, when you go home, when the hikoi finishes today and you go home you got a big, big job. Because we got to keep the kōrero going. It’s so so so important. Because this is a huge part of our history and makes up who we are as Māori today, as New Zealanders, as Kiwis. Koinei ngā kōrero. Koinei ngā kōrero. Nō reira, koina tāku ki a tātou. Don’t forget, remember, and keep telling the stories.’

Nigel Te Hiko:

‘Welcome to Ō-Rākau. What you’re gonna hear today is actually from the stories from the kōrero of those who fought here. And so, you’re gonna hear our story, this is our history, this is our truth.

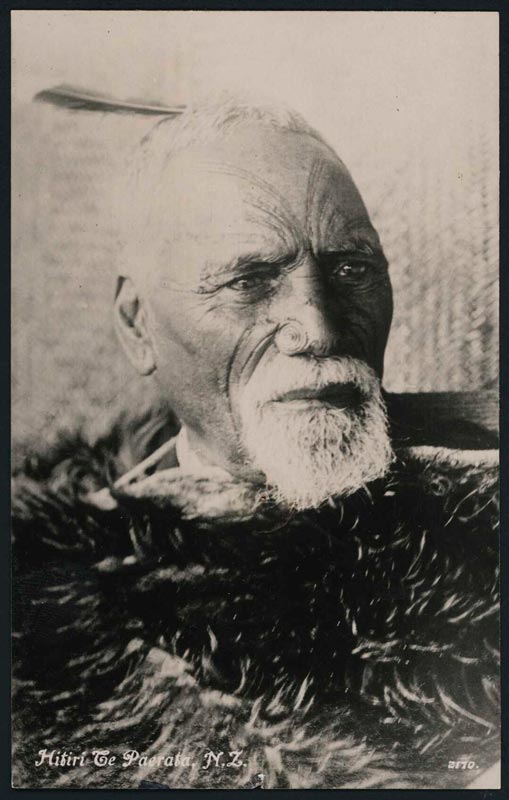

Standing at Ō-Rākau, often it breaks my heart when I stand here. The problem with us not talking about places like Ō-Rākau is that then it becomes easy to forget. It becomes very easy for the Crown or for the Government to forget about what happened in places like Ō-Rākau and Rangiaowhia. I was one of the privileged ones to actually have that kōrero. Me of my generation and the generation before me, weren’t given that opportunity. I think about, if we don’t tell the story, then how are you gonna know. And so, what I am going to give you today is not found in any history book, it is passed on from generation to generation. It was told to me by my koroua and my kuia. When they said it, they had tears in their eyes. My koroua Te Paerata, was so angry that he told his people we are going to go to war. He took his tokotoko and said “Me mate au ki konei” – let me die here on the land.

It was a stinking hot day on the 31 March 1864 but they were having church, when our sentries, our lookouts saw the advance of the British Troops, Lieutenant Brigadier General Careys troops moving upon the pā. The pā was attacked three times, every time the British attacked Ō-Rākau pā, they were repulsed they were pushed back. Three hundred Māori, men, women and children here in this pā, fighting against Carey’s troops of over 1200. For every 1 Māori defender there was 4 trained soldiers. Because we got caught early from finishing the pā, we ran out of food, we ran out of water and we ran out of bullets. It got to such a bad state that what we were putting in the guns, we were putting pips from the peaches that’s what they were using. “Go tell those people that we will give them a chance to get out, to give up”. The reply was “Friend, we will fight you forever, ka whawhai tonu mātou ake”.

So, for many of them it was an act of chivalry, an act of bravery that these young men would give their lives so selflessly.

For my family, we remember Ō-Rākau not only with a sense of sadness, but also with a sense of pride because our koroua Te Paerata, who gave his life here, his son Honeteri gave his life here for the service of his people, and so we remember these people, we remember Ō-Rākau.’

Anthony Pecotic:

'And you got to understand this rain is a blessing, ‘ānei he pai tēnei ua, te honongā Papatūānuku ki Ranginui, Ranginui ki a Papatūānuku ki Ranginui’.

So, my name is Tony, my tupuna who fell here her name was Hinetūrama. Her daughter died with her as well her name was Ewa. But I like to cast my mind back to 1850 to the time we were talking about before at Rangiaowhia, that this whole area was a Pātaka kai.

So, my whakapapa here comes from my tupuna, she lived in Maketu over in Te Arawa, she lived on Mokoia, she lived in Ōhinemutu and she lived in Ō-Rākau. So, she had kainga in all those places and those places connected her to her whenua.

So, Māori we didn’t have one kainga, we had a whole lot of kainga and it followed our whakapapa. So, it was a new land, it was a new time. The Treaty of Waitangi had been signed.

‘Kua tiro rātou whakamua’, they were looking forwards to the time all the pakangā, all the fighting of the past was behind them and this new world was taking them forward.

They knew the pain, they knew the anguish that our people went through just over the hill there. They knew what happened, but they still decided to stay, they still decided to stand.

Te Arawa, just like Ngāti Porou had some people in it that fought with or against the Crown at different times, so it was survival, survival instinct at that time.

The battle went for three days, they ran out of water, they ran out of kai to eat. The babies inside were starving, but when you’re in war, you’re in war and when you’re fighting for your kids, I think you will do anything.

So, I stand here on behalf of my tupuna, that lies here in Ō-Rākau her name was Hinetūrama.

I use to ask my grandmother “why don’t we talk about this”, or ‘“He riri ia”, because I was talking about her great grandmother and she use to say “You don’t know, you don’t understand the pain and I don’t want to give it to you, you don’t need to know this…”

He said “No, no, your mother was an enemy, your sister as well and so then he sent a claim in, claiming all the area that he could whakapapa to.” They said, “no, no it belongs to other people now, your claim is invalid.”

For the rest of his life he continued to try and come back to get his mothers’ bones and they said no, no, no, no Māori not allowed here.

So, we became what’s called ‘“ahi mātao”, so ahi mātao means, that your fires have burnt out, it means you no longer have a home, it means you no longer have a kainga.

Through all these wonderful things we’re doing today, as a part of that coming back that re-connecting, re-connecting on our Raukawa side.

Now if you think about it, the battle that took place where woman and children were killed, it burns a memory on the minds and the hearts of our people, because it wasn’t done by te Ao tāwhito, te Ao Māori, it was done by fellow Christians.’

Kiriupokoiti Heke (Koro Gin):

'The battle was here in 1864, my grandmother that brought me up, she was only 15 year old and they used her to get the water from the Pūniu River, use to fill up these calabashes with water, run all the way down about 4 kilometres down towards the Pūniu River to get the water for them. In 1958, she passed away at 112.’

After failing to take the pā through a direct assault, Carey decided to lay siege to it. General Cameron arrived boosting the Crown’s forces to well over 1400 troops that fully surrounded the pā.

By the 2 April 1864, it became clear that the pā would fall. This prompted Cameron to offer terms of surrender.

Afterwards, some of the Raukawa survivors made their way south towards the safety of the King Country or to Taupō. Others made their way to Tauranga, where they unfortunately found themselves in the middle of a further theatre of war.