The Iwi of Raukawa descends from the eponymous ancestor, Raukawa.

Raukawa is the eldest child of his father Tūrongo of the Tainui waka and his mother, the celebrated Māhina-a-rangi of the Takitimu waka. His birth was significant as a bridge joining the people of the west and east coast of the North Island.

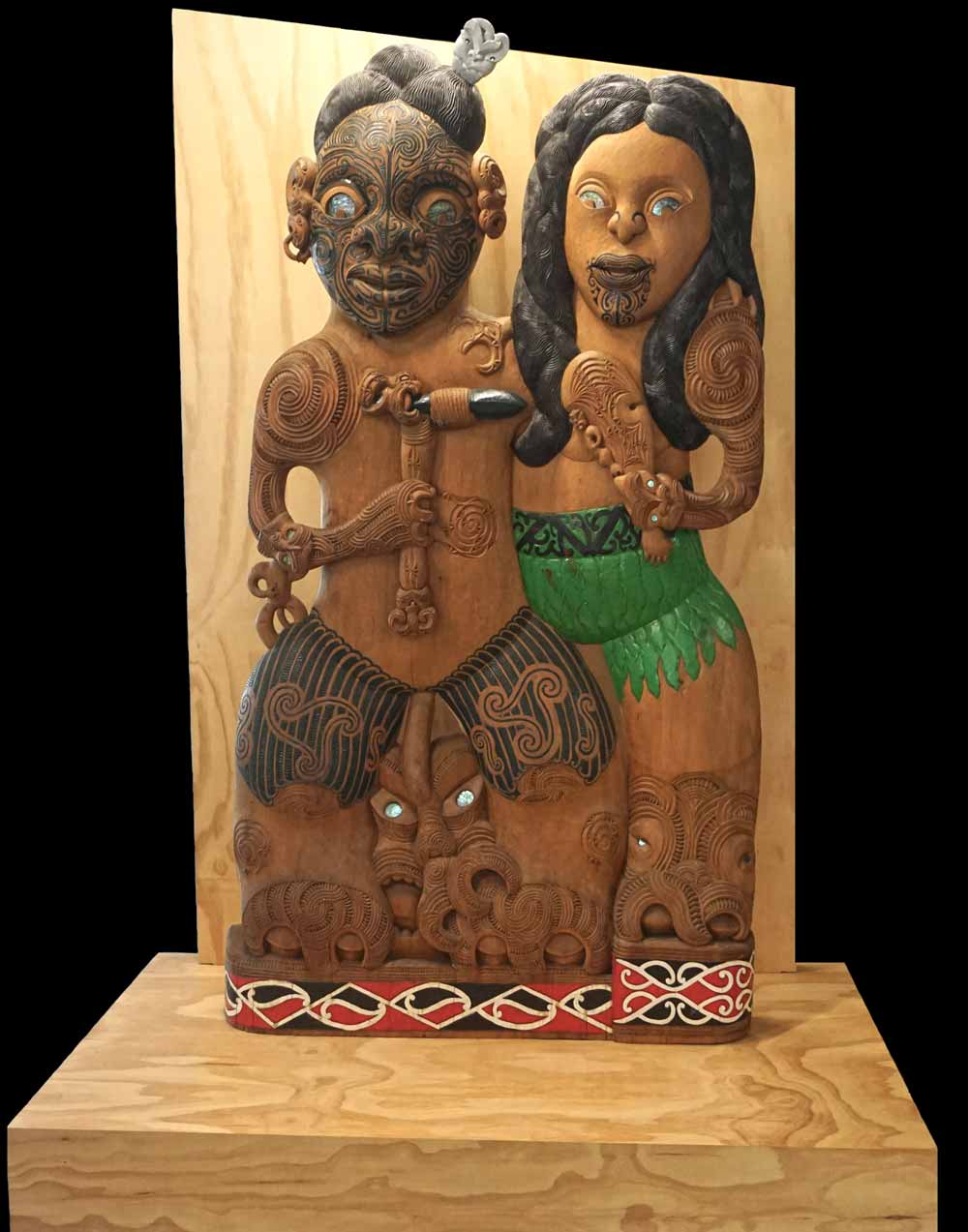

The story of Tūrongo and Māhina-a-rangi is an epic love story.

Their courtship was immortalised in the naming of their son Raukawa. Etched within the cultural memory of the iwi was the journey undertaken by a heavily pregnant Māhina-a-rangi from her lands to her husband’s. This highlighted the determination, strength and courage of our ancestors to set the foundation of the iwi and to create a connection to the land.

Taku ara rā ko Māhina-a-rangi

Video transcript

Taku ara rā ko Māhina-a-rangi. The birth of Raukawa is a very significant story to the iwi.

This kōrero is a summary of the events leading up to and following Raukawa’s birth.

Like most oral histories there are variations to kōrero. This is but one kōrero as described by Raukawa historian and kaumātua Nigel Te Hiko following his research during the treaty settlement process.

The story of Raukawa has been immortalized in the history of the iwi. It was a story built upon true love and principles, sacrifice, obligation, tenacity and duty. It was a true love story that rivalled any great saga ever recorded.

Tūrongo a direct descendant of Hoturoa, the captain of the Tainui waka and Māhina-a-rangi the beautiful maiden of the East coast and descendant of Tamatea-arikinui, the captain of the Takitimu waka.

After suffering a devastating betrayal by his brother, Tūrongo left his homelands in Kāwhia and travelled overland to the East coast.

He had learned of a famed maiden whose beauty was without rival and he sort to pursue her favor.

Arriving at Kahotea the home settlement of Māhina-a-rangi, he set about certain tasks that highlighted his exceptional skills. In his homelands Tūrongo was renowned for being a master builder with excellent communication skills and a great food gatherer. It was not long before his famed skills won over the people of Kahotea.

Māhina-a-rangi’s parents suggested that she might consider Tūrongo as an excellent suitor.

However, little did they know Māhina-a-rangi had already laid plans to court this young chief. She knew where Tūrongo returned to his resting place at night and that his path led him past the spring.

One night under the cover of darkness as Tūrongo made his way to his sleeping place, he passed the spring when he smelt the fragrant aroma of the raukawa oil floating on the clear night breeze and heard the delightful giggle of a young woman. This drew him to her and he was met by an unknown woman who remained hidden by the night.

In a brief encounter they embraced, then the unknown maiden disappeared into the darkness and Tūrongo was left intrigued by the encounter but was determined to discover the identity of the woman.

The only clue to her identity was the scent of the raukawa oil worn by her. With the memory of his previous night’s encounter rushing through his mind, Tūrongo carried on his usual business, but never forgetting the aromatic scent that drew him to the beautiful maiden.

As he was making his way back to his resting place he came across a group of young women playing a game when he smelt the familiar scent of the raukawa oil, it was a scent that had burnt its way into his soul, it was a scent that he would never forget.

The special fragrance of the oil revealed that the beautiful Māhina-a-rangi was the woman that Tūrongo had met the night before. With their identities revealed they both expressed their love for each other, this news was greeted with approval by her parents and her people and shortly thereafter they were joined in union.

Tūrongo and Māhina-a-rangi, continued to enjoy living at Kahotea, until it was announced that Māhina-a-rangi was hapū. Although Tūrongo had enjoyed living with his wife’s people, he yearned one day to return to his homelands. Hearing that his wife was with child, he was determined that he should return to his lands with his new whānau.

After discussing with Māhina-a-rangi, it was agreed that they would return to Tūrongo’s lands. Tūrongo returned to his homelands promising to build a new home for his whānau.

Before leaving, Tūrongo left his kurī Waitete as a guide to help his wife find him as she opted to wait until the pregnancy was more pronounced.

When the time came for her to leave Kahotea, Māhina-a-rangi was late in her pregnancy. She did this because she wanted her people to see the unborn child nesting within her womb and she wanted them to connect to the child.

Māhina-a-rangi and her entourage left Kahotea taking a circuitous route along the East coast.

Every village she passed she was celebrated, along the way her people could see her pregnancy and would connect with the unborn child. The people realized that even though the child would be raised in the West coast, the child was also bound to the people of the East coast.

From Kahotea, Māhina-a-rangi journeyed north to her people at Wairoa. From Wairoa she set off Eastward to her whānau at Waikaremoana, then onto Rotorua.

Her journey then took her to Kuranui the Kaimai-Mamaku track that would take her towards her Takitimu whanaunga in Tauranga Moana. When Māhina-a-rangi reached Kumikumi feeling her labor pains begin, she turned Westward again to ensure her child would be born within the domain of his father.

According to some, Te Pae-o-Raukawa got its name from Māhina-a-rangi, who while crossing the Kaimai Ranges to join her husband Tūrongo, looked out at the lands around her. She could see Maungatautari and Wharepūhunga to the west, as well as the area that came to be known as Te Kaokaoroa-o-Pātetere below her. When looking to the south the young Raukawa kicked within her stomach, to which she said ‘Ka takahia e koe ōu waewae ki runga i Te Pae-o-Raukawa’.

Some people say that at the top of the Kaimai Ranges, in a place known as Whenua-ā-kura, she gave birth to the new ariki. The child was named Raukawa in recognition of the aromatic scent worn by his mother during the courtship of his parents.

From Whenua-ā-kura, Māhina-a-rangi came down the track known as Te Ara Pōhatu into the Pātetere region.

The naming of numerous places within this area reflect the birth of Raukawa.

Rapurapu stream takes its name as referenced to the cleaning of the afterbirth from the new born child.

Māhina-a-rangi fed her new baby at the base of the Kaimai Ranges an event commemorated at the naming of the original Ūkaipō marae.

Te Poipoitanga a Raukawa or Te Poi as it is more commonly referred to celebrate the nurturing of the new born child.

Within this area, Māhina-a-rangi took time to recover from giving birth. She utilised the hot springs found throughout the area particularly bathing in the warm waters of Waitakahanga a Māhina-a-rangi, commonly referred to today as ‘Māhina-a-rangi’s bath’. These hot pools helped to rejuvenate her strength before moving on towards Maungatautari that she saw in the distance.

Arriving at the narrowest part of the Waikato river just at the foot of Maungatautari at a place called Ānewanewa, Māhina-a-rangi crossed the Waikato river. Once across she undressed the swaddling cloth from the baby and laid it out to dry. This became known as Te Horahoratanga o Ngā Maro o Raukawa, more commonly known today as Horahora.

Having returned to familiar territory the kurī, Waitete left the group at Parahaemotu to find his master Tūrongo. Upon seeing the dog arrive at his new pā, Tūrongo knew that his wife was coming, he immediately set off to find them.

At Pirongia, Tūrongo had found his wife and new born son waiting for him. Excited they continued their journey to the newly built pā of Rangiātea, upon arriving they were greeted by the great chief Tāwhao the father of Tūrongo to their new home on the banks of the Mangaorongo river. It was here that Tāwhao performed the tohi ceremony on his grandson confirming the name Raukawa upon the child.

This story provides insight into the journey traversed by our tūpuna Tūrongo and Māhina-a-rangi. It is a journey of significance to the Iwi of Raukawa embedded within our stories, our memories and our named landmarks. It expresses the practice of values from the past and the continued adherence to them by the present to guide the future generations of Raukawa.