Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi: Man goes before, land Remains

Chapter 2

Rauru goes before but the land remains

By 1873, Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi were virtually landless, victims of a ‘scorched earth’ policy.

Explore Chapter 2

Video transcript

In 1840, the estate of Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi spanned 520,000 acres- land, rivers, seabeds. From the Paatea river, to Te Kaihau a-Kupe, and north to Matemateaaonga.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi amassed support from over 500 signatories across the country but Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi was not among them.

Copies of Te Tiriti were dispersed throughout the North and South Islands, however, no copy made it further north of Whanganui nor south of Kaawhia. But whether or not Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi had signed Te Tiriti o Waitangi was irrelevant. The British Colonial Office ruled that all Maaori were British subjects, and were therefore subject to Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

In 1841, William Spain was appointed the New Zealand Land Claims Commissioner. He was tasked with investigating the New Zealand Company’s land purchases. The Company claimed it had purchased some 20 million acres since 1839, including a 40,000 acre block of land between the Kai Iwi and the Whangaehu Rivers, known as the Whanganui Block.

The Deed of Purchase for the Whanganui Block recorded a receipt of goods in exchange for extremely valuable land.

Settlers were arriving in their droves to occupy the new lands, despite many of those purchases were being contested by Maaori.

The majority of the Company's claims, especially those at Nelson, Wellington and Whanganui, did not appear legitimate. However, Spain did not declare the land sales invalid. He awarded £1,000 as further compensation to all iwi that were involved with the purchase.

Within five years, the 40,000 acre block had more than doubled. By the time the Crown completed the purchase in 1848, the New Zealand Company had acquired 89,000 acres at Whanganui- more than twice the amount granted by Spain. [He Whiritaunoka (2015).]

20,000 acres of that purchase sat within the boundaries of Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi.

Pootonga Neilson, kaumaatua, Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi:

‘It was not in their psyche to actually sell land, so what they actually sold to the Paakehaa was the right to dwell within that block, Whanganui Block, as long as they remained peaceful and respectful to the local people, that was fine. But they weren’t able to do that.

When it came to the Kai Iwi Block, they put the price up but you’ve got to remember, every one of those transactions was hotly disputed by one section, supported by another section, and others who didn’t know.

So at Kai Iwi they had a visit from Makarini, Donald McLean, the Crown land agent.’

Donald McLean became the Chief Land Purchase Commissioner in 1853, in a period when Maaori were strongly opposed to selling land.

Pootonga Neilson, kaumaatua, Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi:

‘There were people at Kai Iwi who were keen to sell and get some money. There were people at Kai Iwi who resisted the sale.

Makarini was informed that the Paakehaa must cease drawing imaginary lines on the land which divide up the people, and the land is not for sale, but there was always a group, and just like the Waitangi Tribunal process, the whole process became very divisive amongst our people.’

Soon, he began to pay hapuu leaders, with the hope they would persuade other land rights holders to sell their interests too. McLean also promised the leaders individual Crown grants if the purchases were completed. McLean’s actions provoked mounting tension.

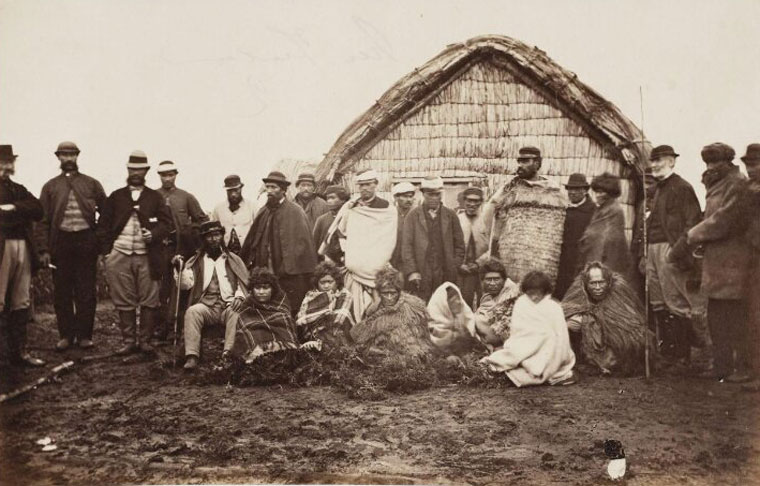

Increasing tensions over the sale of Maaori land led to a conference in 1854 between Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi, Ngaati Ruanui and other Taranaki iwi at Manawapou, north of Paatea.

At least 1,000 people gathered at the meeting. The purpose was to discuss tribal boundaries and to encourage hapuu to cease selling land to Europeans.

Pootonga Neilson, kaumaatua, Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi:

‘They made an agreement to that effect. And the big meeting house they built especially for this gathering was called Te Taiporoheenui. They also had a toki (adze). That toki was the symbol of the agreement of the anti-land league which did exist. There would be no more land sales within Taranaki.’

But in 1858, Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi withdrew from the Manawapou agreement.

Reverend Richard Taylor resided at Puutiki, Whanganui. He was well respected by Maaori throughout the region. He became the peacemaker between Maaori factions, as well as Maaori and settlers. He also acted as a spokesperson for dealings with the Government.

According to Taylor, some Ngaati Ruanui who had 'a kind of a claim' to Waitootara said they would give it to the Maaori King. Taylor wrote to inform McLean:

‘This so offended the real owners that although previously they had no intention of selling it, they exclaimed, “who are you who presume to dictate to us what we shall do with our lands?”’

Aaperahama Tama-i-parea was one of seven rangatira of Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi who despised the selling of land to the settlers. But when Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi met with the representatives of the Maaori King, they were so incensed at being told what to do with their land that Aaperahama and his son, Pehimana, decided to sell the Waitootara Block to the Government.

McLean granted a £500 deposit for the Waitootara Block in May, 1859. The receipt recorded only 14 signatories.

Before the sale could be finalised, war broke out in north Taranaki in 1860. Unarmed Maaori, mostly women, tried to prevent the Crown’s attempts to survey the Pekapeka Block at Waitara. This was considered an act of rebellion. The Crown proclaimed martial law in February 1860 - the beginning of the first land wars in Taranaki. Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi and other Taranaki iwi rallied to support Te Aatiawa in the war against the Crown.

After 14 months, a peace agreement was reached. The Crown resumed negotiations regarding the Waitootara Block in 1862.

By this time, Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi no longer wanted to sell the land but the Crown continued to negotiate with those who were part of the earlier agreement. Eventually, the sale of the Waitootara Block concluded in July 1863.

Four of the original 14 signatories from 1859 signed again in 1863, alongside an additional 28 signatories.

£2,000 changed hands. 26,638 acres were alienated from Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi through this purchase.

Aaperahama's name did not appear on the final deed of sale. He protested, “The land shall not be given up! Never! Never! Never!” He rejected the sale and joined other chiefs at Weraroa Paa on the Waitootara River.

Pootonga Neilson, kaumaatua, Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi:

‘The Waitootara Block was the catalyst for the real war in South Taranaki. The Waitootara Block was eventually sold by some of our people and others resisted hence the arrival of the Pai Maarire, who became the Hauhau, who became the rebellious savages who needed to be eliminated.’

Under the New Zealand Settlements Act 1863, the Crown confiscated land from any Maaori who acted against the authority of the Queen of England. This single Act legalised the theft of Maaori land by the Crown.

In January 1865, General Cameron’s forces, 2,000 soldiers strong, advanced north-west from Whanganui to take possession of the Waitootara Block for the Crown.

Governor George Grey was determined to end the Pai Maarire threat in Whanganui and South Taranaki. His immediate concern was to take Weraroa Paa, and its stronghold of 2,000 Maaori. Several hundred Hauhau from the Whanganui to Waitara assembled, inspired by the presence of their prophet Te Ua Haumene. [Cowan (1956), p. 46]

Cameron refused to attack Weraroa. He was critical of what he saw as “colonial land-grabbing” and “the use of Imperial forces to achieve this””. ['Duncan Cameron' (NZHistory)]

This led to a breakdown in his relationship with Grey. Grey took it upon himself to lead the advance on Weraroa. He seized and occupied Weraroa in July.

Pootonga Neilson, kaumaatua, Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi:

‘Now what happened to our people in that period was what the Government called the ‘bush scouring’ period, which was actually a ‘scorched earth’ policy. And it’s well documented that they went up all the rivers within Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi and Taranaki where the bulk of the population lived. And they destroyed everything, and looted everything. And our people were forced to live in isolation in the bush for years in some cases.

The really sad thing is what happened to our people during that bush scouring expedition. There were many of them. They went up the main rivers, more than once they went up there, and harassed and terrorised our people, most of whom had never even participated in the land wars.

And it was only when Keepa, Major Kemp, came to Waitootara and found 500 of our tuupuna living on Pootiki-aa-Rehua. And the Paakehaa living in Waitootara saying, ‘If you come back to Waitootara, you’ll be shot on sight’. And they sent a letter to the ones living at Tawhitinui on the Whanganui River, ‘do not come back to Waitootara, you’ll be shot on sight’. Major Kemp had to come as one of the people responsible for the removal of our people from their whenua and he had to talk on their behalf and work on their behalf so that they could come down from their refuge on top of Pootiki-aa-Rehua.’

Many, displaced from their lands since 1865, pledged loyalty to the Crown so they could return to their homes.

Pootonga Neilson, kaumaatua, Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi:

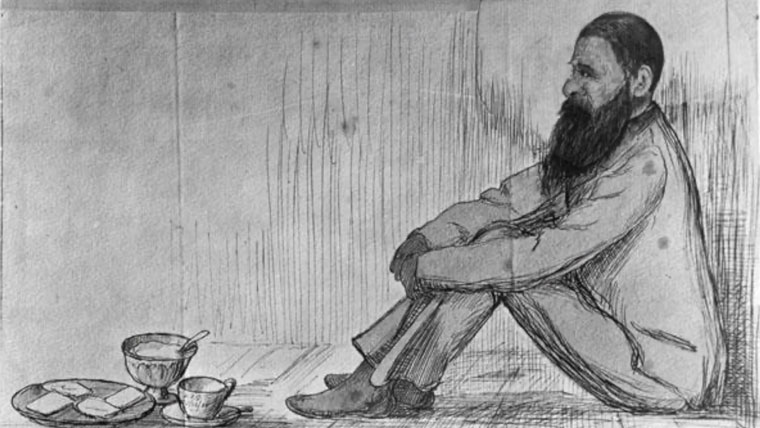

‘Behind me here on this wall is a picture of all the able-bodied men in 1865, arrested to discourage rebellion. In their mind, they hadn't seen the treaty, they hadn’t signed the treaty so rebellion must be a false charge. All the able bodied men in that picture from Waitootara here, were arrested up on Weraroa, the fortified paa on top of the hill before you come down to the Waitootara, and they were taken down south. They were kept as prisoners on a prison hulk in the Wellington Harbour, and then taken down to Dunedin. They were looked down on as rebels and savages and charged with that crime.

For me, instead of being branded rebels and savages, they should be given as much recognition as we give the veterans of World War I and World War II. They were patriotic people.’

The campaign against the Hauhau continued until the end of 1867.

Meanwhile, a storm was brewing in South Taranaki.

In June 1868, the confiscation of large amounts of land for European settlement led Tiitokowaru to wage war against the Crown and settlers. Fighting ensued at Maawhitiwhiti, Turuturumookai, Te Ngutu o te Manu, Moturoa, and Nukumaru.

Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi villages and cultivations up the Waitootara River were devastated in retaliatory raids against Tiitokowaru by government troops. The Crown pushed Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi further and further out of South Taranaki, and pursued them into the interior.

Pootonga Neilson, kaumaatua, Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi:

‘You hear a lot about the Waitara end but there is not that much printed or written about the wars here. We know very little about it. We know very little about the hundreds of our people who were driven off into the bush and had to survive, and had all their resources burnt or stolen. So, we really don’t know what they went through and we don’t know how many died in that process. They were harassed by what I would call today, a terrorist government.

It all became a terrible - it was a holocaust. It was a damn holocaust that our people went through. What happened to the women and children who were driven off their papakaainga? And their crops burned and everything and they had to live in the bush for years? We don’t know. How many of them died there? This is our history.’

On 27 November 1868, a colonial militia led by Lieutenant Bryce and Sergeant Maxwell, encountered a group of unarmed Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi and other Taranaki iwi children at Handley’s Woolshed, near Tauranga Ika marae at Nukumaru. The children were from the Tauranga-Ika Paa, the eldest of whom was about 10 years old.

Mike Neho, kaumaatua, Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi:

‘A group of soldiers went inland to chase Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi. Upon their return to Whanganui, they saw some children moving about. They went to see what that movement was. The thought occurred to them to go and bother the children so they went- no it wasn’t to bother them but to scare them. So that’s what happened. Some drew their swords and cut the hand of one of the children. That was the circumstance of one of the wounded. They returned to Whanganui. Eventually, the name ‘Maxwell’ was bestowed upon that place. Now, this Maxwell, he was the person that assaulted our children.’

In an unprovoked attack the militia fired on the group, pursued them on horseback, and attacked them with sabres. The children were wounded. Two were assaulted and killed.

In February, 1869, Tauranga Ika was abandoned by Tiitokowaru.

Until 1873, Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi were forbidden to return to their home.

By the time they could come home there was barely anything to come home to.

They were deemed rebels.

The land was gone.

Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi did not sign Te Tiriti o Waitangi but that was irrelevant to the Crown.

The British Colonial Office ruled that all Maaori were British subjects, and were therefore subject to Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

The British assumed they had control over the land, appointing a commissioner, William Spain, to investigate the New Zealand Company’s land purchases.

Commisioner William Spain and The New Zealand Company

In 1841, William Spain was appointed the New Zealand Land Claims Commissioner.

He was tasked with investigating the New Zealand Company’s land purchases.

The Company claimed it had purchased some 20 million acres since 1839, including a 40,000 acre block between the Kai Iwi and Whangaehu Rivers, known as the Whanganui Block.

16 November, 1839.

Deed 421 - WHANGANUI BLOCK

Purchase of New Zealand Land Company.

Know all men by these presents that we the undersigned chiefs of the District of Wanganui, situated on the north shore of Cook's Straits, in New Zealand, have this day sold and parted with all our right title and interest in all the lands, islands, tenements, woods, bays, harbours, rivers, streams, and creeks, within certain boundaries.

As shall be truly described in this deed, or instrument unto William Wakefield Esquire, in trust for the governors, directors and shareholders of the New Zealand Land Company of London, their heirs, administrators, and assigns, for ever in consideration of having receipt received, as a full and just payment for the same;

140 White Blankets

100 Red Blankets

10 Double barrelled Fowling Pieces

6 Single barrelled Fowling Pieces

30 pea Jackets

30 pairs Flushing Trowsers

30 fustian Jackets and pairs of Trowsers

2 dozen pairs of Shoes

6 dozen Shifts and Shirts

6 doz red Woollen Shirts and Caps

1 dozen Comforters

6 Camlet Cloaks

2 doz. Petticoats

12 duck Frocks and pairs of Trowsers

10 doz. Pocket Handkerchiefs

30 chintz Dresses

200 yards of Calico

200 yards of Check

50 powder Horns

18 powder Flasks and shot Belts

18 bullet Moulds

1,000 Flints

20 lead Slabs

50 casks of Gunpowder

2 casks Ball Cartridge

100 Tomahawks

18 Cartouche Boxes

3 quires Cartridge Paper

1 case of Pipes

18 Umbrellas

30 thrasher Hats

2 dozen Hoes

4 dozen Axes

15 Tinder-boxes

3 doz. Tin pots

6 doz. Looking Glasses

2 lbs Sealing Wax

2 lbs. Beads

6 doz. Combs

3 doz. Shaving boxes

2 doz. Slates and 200 Pencils

6 doz. Pocket knives

6 dozen Razors

2 doz. Spades

2,000 Fish Hooks

50 Iron Pots

2 tierces of Tobacco and 1 case of Soap……which we the aforesaid chiefs do hereby acknowledge to have been received by us from the aforesaid William Wakefield.

Settlers were arriving in their droves to occupy the new lands, despite many of those purchases being contested by Maaori.

...the majority of the Company's claims, especially those at Nelson, Wellington and Wanganui, did not hold up. However, Spain did not declare the land sales invalid.

Spain awarded £1,000 as further compensation to all iwi involved with the purchase.

Within five years, the original 40,000 acre block more than doubled.

By the time the Crown finalised the purchase in 1848, the New Zealand Company had acquired 89,000 acres at Whanganui - double the amount granted by Spain.

20,000 acres of that purchase sat within the traditional boundaries of Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi.

Pootonga Neilson, kaumaatua of Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi, provides some insight:

They did not bid farewell to the land because they did not sell off the land.

It was not in their psyche to sell land, so what they actually sold to the Paakehaa was the right to dwell within that block, Whanganui Block.

As long as they remained peaceful and respectful to the tangata whenua, kei te pai teenaa engari e kore e taea i teeraa mea.

Tension over land purchases

Further land purchases at Kai Iwi, Aokehu (Ookehu), and Waitootara soon followed.

By 1853, when Donald McLean became the Chief Land Purchase Commissioner, Maaori across the country strongly opposed selling land.

Neilson adds;

Makarini (Donald McLean) was informed that the Paakehaa must cease drawing imaginary lines on the land which divide up the people, and the land is not for sale, but there was always a group, and just like the Waitangi Tribunal process, the whole process became very divisive amongst our people.

Increasing tensions over the sale of Maaori land led to a conference in 1854 between Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi, Ngaati Ruanui and other Taranaki iwi at Manawapou, north of Paatea. At least 1,000 people gathered at the meeting to discuss tribal boundaries and encourage hapuu to stop selling land to Europeans. The meeting was called Taiporoheenui.

But in 1858, Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi withdrew from the Manawapou agreement.

Reverend Richard Taylor, based at Puutiki, Whanganui, was a clergyman who was well respected by Maaori throughout the region. He became the peacemaker between Maaori factions, as well as Maaori and settlers. He also acted as a spokesperson for dealings with the government.

According to Taylor, some Ngaati Ruanui who had ‘a kind of a claim’ to Waitootara said they would give it to the King (Pootatau Te Wherowhero). Taylor wrote [to McLean]:

‘This so offended the real owners that although previously they had no intention of selling it they exclaimed, “who are you who presume to dictate to us what we shall do with our lands?”’

Aaperahama Tama-i-parea was one of seven rangatira of Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi who despised the selling of land. But after meeting with representatives of the Maaori King, Aaperahama and his son Pehimana were so incensed at being told what to do with their land they decided to sell the Waitootara Block to the Government.

To secure the purchase, McLean granted a £500 deposit in May 1859. Only 14 signatories were recorded on this receipt.

Before the sale was finalised, war broke out in north Taranaki in 1860. Unarmed Maaori, mostly women, had tried to prevent the Crown from surveying the Pekapeka Block at Waitara. The Crown considered this an act of rebellion and proclaimed martial law in February 1860 - the beginning of the land wars in Taranaki.

Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi and other Taranaki iwi rallied to support their kin in the north. After 14 months, a peace agreement was reached.

The Crown resumed negotiations regarding the Waitootara Block in 1862. By this time, Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi no longer wanted to sell the land but the Crown continued to negotiate with those who were part of the earlier agreement. The sale of the Waitootara Block concluded in July 1863. Four of the 14 people who had signed in 1859, signed again in 1863, with 28 other signatories.

£2,000 changed hands and 26,638 acres were alienated from Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi.

Aaperahama's name did not appear on the final deed of sale. He protested, “The land shall not be given up! Never! Never! Never! Never!”

He rejected the sale and joined other chiefs at Weraroa Paa on the Waitootara River.

The Waitootara Block was the catalyst for the real war in South Taranaki. The Waitootara Block was eventually sold by some of our people and others resisted hence the arrival of the Pai Maarire, who became the Hauhau, who became the rebellious savages who needed to be eliminated” exclaims Neilson

Weraroa Paa – The Hauhau

Under the New Zealand Settlements Act 1863, the Crown had the power to confiscate land from any Maaori who acted against the authority of the Queen of England. This single Act legalised the theft of Maaori land by the Crown.

In January 1865, General Cameron’s forces, 2,000 soldiers strong, advanced north-west from Whanganui to reclaim the Waitootara Block for the Crown. Several battles were fought at Nukumaru against the Hauhau.

Governor George Grey was determined to end the Pai Maarire threat in Whanganui and South Taranaki. His immediate concern was to take Weraroa Paa, and its stronghold of 2,000 Maaori.

Cameron, however, refused to attack Weraroa paa. He was critical of what he saw as “colonial land-grabbing and the use of Imperial forces to achieve this”.

As a consequence, Cameron’s inaction at Weraroa led to a breakdown in his relationship with Grey. Grey instead took it upon himself to lead the advance on Weraroa Paa, whilst Cameron continued up the coast to Paatea. In July, Grey seized and occupied Weraroa.

For Neilson, the images on the walls of this wharenui are reminders of the horrific actions carried out by the Government:

Behind me here on this wall is a picture of all the able-bodied men in 1865, arrested to discourage rebellion.

In their mind, they hadn't seen the treaty, they hadn’t signed the treaty, so rebellion must be a false charge.

All the able bodied men in that picture from Waitootara here, were arrested up on Weraroa, the fortified paa on top of the hill before you come down to the Waitootara, and they were taken down south. They were kept as prisoners on a prison hulk in the Wellington Harbour, and then taken down to Dunedin.

They were looked down on as rebels and savages and charged with that crime. For me, instead of being branded rebels and savages, they should be given as much recognition as we give the veterans of the WWI and WWII. They were patriotic people.

The campaign against the Hauhau continued until the end of 1867.

Many displaced from their land since 1865 pledged loyalty to the Crown so they could return to their homes.

South Taranaki wars

Meanwhile a storm was brewing in South Taranaki.

In June 1868, the confiscation of large amounts of land for European settlement led to what became widely known as Tiitokowaru’s War.

Fighting ensued at Maawhitiwhiti, Turuturumookai, Te Ngutu o te Manu, Moturoa, then Taurangaika at Nukumaru.

On 27 November 1868, a colonial militia led by Lieutenant Bryce and Sergeant Maxwell, encountered a group of unarmed children of Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi and other iwi of Taranaki at Handley’s Woolshed, near Waitootara.

A group of soldiers went inland to chase Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi. Upon their return to Whanganui, they saw some children moving about. They went to see what that movement was. The thought occurred to them to go and harass the children so they went - no it wasn’t to harass them but to scare them. So that’s what happened.

Some drew their swords and cut the hand of one of the children. That was the circumstance of one of the wounded. They returned to Whanganui. Eventually, the name ‘Maxwell’ was bestowed upon that place. Now, this Maxwell, he was the person that assaulted our children.

The children were from Tauranga-Ika Paa; the eldest about 10 years old. In an unprovoked attack the militia fired on the group, pursued them on horseback, and attacked them with sabres. The children were wounded and two were killed.

Crown forces pushed Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi out of South Taranaki, and pursued them into the interior. Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi villages and cultivations up the Waitootara River were devastated in retaliatory raids against Tiitokowaru by government troops.

Until 1873, Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi were forbidden from returning to their home. By the time they came home there was barely anything to come home to.

They were deemed rebels.

Ngaa Rauru Kiitahi were virtually landless.

Notes and credits

Main image at top of page: View of the Matemateaaonga Ranges atop Whakaihuwaka (Mt Humphries). Credit: Jim Campbell, Te Papa Atawhai DOC Whanganui